Introduction

Pleural effusion is the excessive accumulation of fluid in the pleural space, indicating an imbalance between the pleural fluid formation and removal. Pleural effusion is not considered as an individual disease, but it is often a complication of an underlying pathology. It may result from the pathology of lung, heart or any system. Potential mechanisms of increased interstitial fluid in the lungs are probably due to increased pulmonary capillary pressure (eg:- heart failure) or permeability (eg :- pneumonia); decreased intrapleural pressure (eg:- atelectasis); decreased plasma oncotic pressure (eg:- hypoalbuminemia); increased pleural membrane permeability and obstructed lymphatic flow (eg:- pleural malignancy or infection); diaphragmatic defects (eg:- hepatic hydrothorax); and thoracic duct rupture (eg :- chylothorax).1

The mean amount of pleural fluid in a normal individual is as small as 8.4±4.3 ml, which is increased in the case of pleural effusion.2 Pleural effusion may be broadly classified as (a) Transudative and (b) Exudative pleural effusion. To treat pleural effusion appropriately, it is important to determine its cause. For which the nature of the fluid (i.e. Transudate or Exudate) has to be determined.

Transudative Effusion

This type is caused by fluid leaking into the pleural space as a result of either low blood protein content in the blood vessel or increased hydrostatic pressure in the blood vessels. Its most common cause is congestive heart failure. It has low protein content.

Exudative Effusion

This type is caused by blocked lymph or blood vessels, inflammation, tumours, lung injury. Common conditions that could result in this type of pleural infusion include pulmonary embolisms, pneumonia, and fungal infections. It has high protein content.

The following research aims at determining the cause of pleural effusion based on laboratory characteristics of the fluid and bring out the diagnostic accuracy of materials used in ascertaining the nature of the fluid to approach a case of pleural effusion.

Materials and Methods

This study was done in the Saveetha medical college, Thandalam in 10 0 patients having pleural effusion. The period of study was from July 2018 to December 2018. The patient were completely examined and a clear history were taken. Clinical history, signs and symptoms gives an idea about the etiology and the probable system involved. Further investigations were done through.

Chest Radiography – Bilateral/Unilateral Effusions

Thoracic ultrasonography (TUS)

Computed Tomography

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Positron emission tomography scan

Once the provisional diagnosis has been made, the pleural fluid is drawn for laboratory investigations and analysis.

Thoracocentesis

Diagnostic thoracocentesis must be performed if the thickness of the pleural fluid on decubitus radiograph, TUS or the CT scan is greater than 10mm.1 Thoracentesis should be concerned under the following conditions: not bilateral and comparable sized effusions; pleuritic chest pain; febrile; and no responses to diuretics.

The main contraindication of thoracentesis is a haemorrhagic diathesis.

Thoracocentesis is performed at eighth, ninth or tenth intercostal space along the midaxillary line. The person is positioned sitting upright with arms raised and supported. A local anaesthetic is applied and then the healthcare practitioner inserts the needle into the chest (pleural) cavity and the sample is removed. Approximately 20 − 40 mL of fluid that is aspirated should be immediately placed into appropriate anticoagulant (EDTA or heparin) coated tubes for biochemistry (5 mL), microbiology (5−10 mL), clinical pathology (10−25 mL), and heparin coated syringe for the pH measurement. Pleural fluids should be analysed within 4 hours of extraction.1

Inclusion Criteria

Patients with pleural effusion determined by clinical and or radiological means, who yield a minimum amount of fluid enough to carry out routine tests, were included in the study.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients with pleural effusion with non aspirable fluid quantity decided clinically or radiologically, were excluded. All these patients underwent detailed clinical examination and routine laboratory examination like blood test for haemoglobin, total WBC count, differential WBC count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, random blood sugar, serum proteins, urine examination, sputum examination and tuberculin test.

Further classification into Exudates and Transudate samples were done based on the following criteria.

Light ’s Criteria for Exudate (Gold standard): 3

Pleural fluid protein to serum protein ratio > 0.5

Pleural fluid LDH to serum LDH ratio > 0.6

Pleural fluid level > 2/3 of upper value for serum LDH

At least one or more of the above criteria must be present.

Research Criteria

Transudative and Exudative effusions were classified based on the biochemical analysis using the values of Total proteins in g/dl. Transudate and exudate have the total protein values of <3 g/dl and >3 g/dl respectively. [Table 1] This served as the major criteria in classifying the fluids. Light’s criteria is the gold standard to differentiate the transudate and exudate over the last three decades. However, the concentrations of the biochemical components (protein, LDH, and albumin) in pleural fluids increase progressively during the diuretic therapy of patients with congestive heart failure according to a recent study.2 Hence there tends to be a misclassification.

The gross appearance of pleural fluid also serves in distinguishing fluids. A reddish pleural fluid indicates that the blood is present (malignant disease, trauma, or pulmonary embolization). Reddish colour of pleural fluid is generally seen in Exudative effusions while Pale yellowish fluid is seen in Transudative effusions. However the findings tend to vary and therefore colour of the pleural fluid serves only as a minor criteria for the above classification.

Other variations in colour can also be observed. For example; Black pleural fluids are pleural infections with Aspergillus niger or Rhizopus oryzae, or following massive bleeding due to metastatic carcinoma and melanoma.1

Results

The study was performed at Saveetha Medical College, Tamil Nadu. The study aims at comparing between transudative and exudative effusions and also determining the predominant age group and gender prevalence among the cases of pleural effusion.

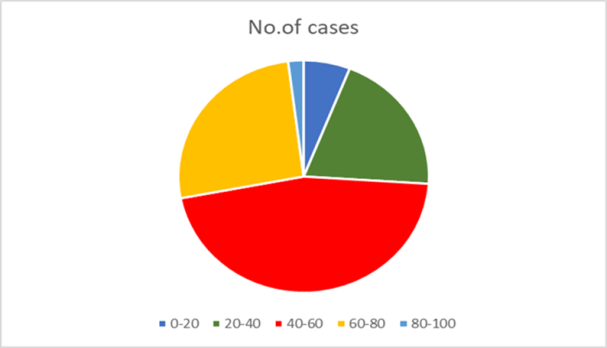

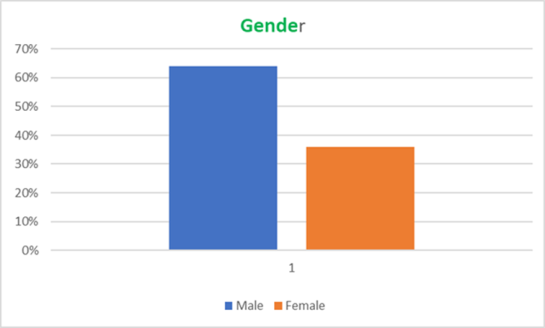

The age and gender co-relation has been tabulated for hundred cases of pleural effusion taking into consideration all the causes of effusion. Results showed a male predominance. Maximum number of cases were reported between age group of 40-60 years of age. [Table 2]

The age group 40-60 years accounts for 46% of the total number of cases. [Figure 1]

Percentage of male pleural effusion cases was found to be 64% compared tothat of females which was 36%. [Figure 2]

The total number of cases chosen for the study is 100. Of which nine cases had unknown causes of pleural effusion. The rest ninety one cases were confirmed cases of pleural effusion with an underlying pathology. [Table 3]

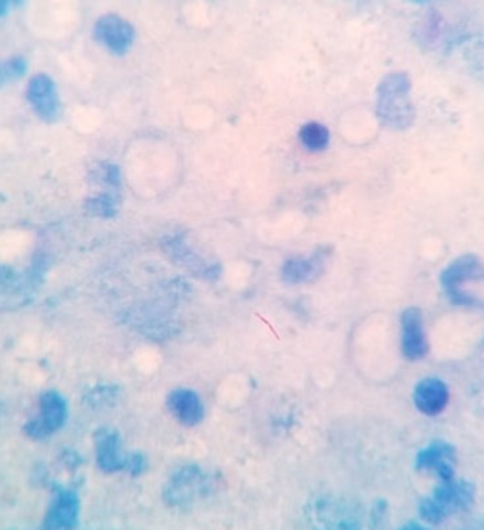

Of which, 34% of cases (i.e. 34 cases) were of Pulmonary Tuberculosis. Tuberculous pleural effusion (TPE) results from Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of the pleura and is characterized by an intense chronic accumulation of fluid and inflammatory cells in pleural space. TPE is the second most common form of extrapulmonary tuberculosis and a common cause of pleural effusions in endemic tuberculosis areas.4 Ziehl neelson stain is used to demonstrate the acid fast tubercle bacilli in the pleural fluid. Mycobacterium tuberculosis appears as reddish-pink coloured rods against a blue background. Pus cells are also visualised. [Figure 3]

The probable causes of pleural effusion for the nine unknown cases of pleural effusion were done based on the research criteria and were categorized as Transudate and Exudate. Of which three were transudative and six were exudative.

The exudative effusions can be further classified based on the differential counts as Lymphocyte predominant, Neutrophil predominant and Eosinophil predominant, and the probable diagnosis was made out. If exudate is confirmed, further testing is required to evaluate the cause of exudate. Causes of exudate was evaluated on the basis of Differential Cell Count. (predominance of white cells) [Table 4]

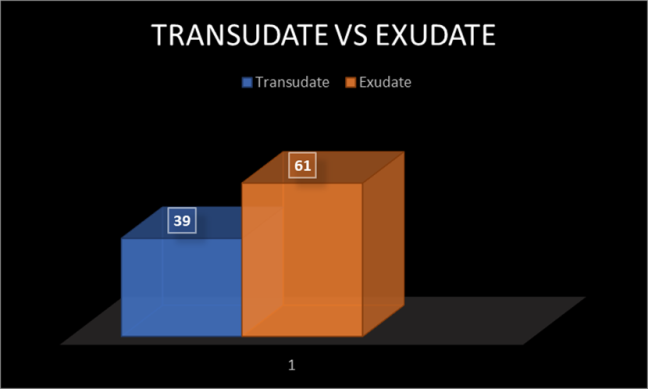

According to the data, thirty nine cases of transudative pleural effusions and sixty one cases of exudative pleural effusions were recorded. [Figure 4]

From the known causes of pleural effusion, certain rare conditions like Meigs Syndrome was observed. Meigs syndrome is a triad of benign ovarian tumour, ascites and pleural effusion. Out of hundred cases, 1% cases were reported with this condition. Although the prevalence of the syndrome is low, it has an important clinical implication.5

According to the research the second most common case of pleural effusion was reported in CKD patients with about 28% of the total number of cases. Pleural disease is a common problem in patients with chronic renal insufficiency.6 There are several reasons why pleural disease may be common in patients with chronic kidney disease. These include congestive heart failure, fluid overload, an increased risk of infection (Especially tuberculosis), the presence of diseases associated with renal and pleural manifestations (e.g., systemic lupus erythematosus), uremic pericarditis, an increased risk for certain malignancies and pulmonary embolism.

The common etiology for pleural effusion include Tuberculosis, Malignancy and CKD according to the current study.

Table 1

| Type of effusion | Total protein (g/dl) [Major] | Colour [Minor] |

| Transudate | <3 | Pale yellow |

| Exudate | >3 | Reddish |

Research criteria

Table 2

| Age group | Male | Female | No. of Cases |

| 0-20 | 1 | 5 | 6 |

| 20-40 | 14 | 6 | 20 |

| 40-60 | 30 | 16 | 46 |

| 60-80 | 19 | 7 | 26 |

| 80-100 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 64 | 36 | 100 |

Age and gender co-relation

Table 3

Total cases of pleural effusion

Table 4

Classification of exudate based on DLC

Discussion

In the current study, pleural effusions were found to be common among 40-60 years of age group. According to a study done by Pujan Parikh et al,7 pleural effusions were more common in 31-40 years of age group In a study done by Kushwaha et al8 it was among four years to 75 years of age group. The results correlated well with the previous study and hence the current research comes to the conclusion that there is an increase in the median age for incidence of pleural effusions. The male: female ratio in the present study was found to be 16:9, which is comparable to study of Pujan Parikh et al (2:21:1).

According to the study, exudate was predominant to transudate with the former having a percentage 61% and the latter with 39%. This is comparable with the previous studies done by Pujan Parikh et al,7 Valdes et al,9 Ram et al10 and Kataria et al11 all of which comment that exudative pleural effusions are more co mmon than the transudative type as shown in [Table 5]. Exudative effusions is common in India which suggests us to look upon the main etiological factors for pleural effusion in India. The present study shows Pulmonary Tuberculosis and CKD to be the main etiological factors. Of which Pulmonary TB is more prevalent in India having exudative etiology.

Comparable with the study done by Pujan Parikh et al, the above finding co r relates with previous study suggesting the importance of pleural fluid analysis in tuberculosis. The World Health Organisation (WHO) TB statistics for India for 2016 gives an estimated incidence figure of 2.79 million cases of TB for India.12 The TB incidence is the number of new cases of active TB disease during a certain time period (usually a year). Based upon the facts and data, an exudative effusion with lymphocytes predominant is highly suggestive of tuberculosis. Confirmation can be done by culture, acid fast staining and GeneXpert.

Conclusion

Diagnosis begins with the clinical history, physical examination, and chest radiography and is followed by thoracentesis when appropriate. To conclude the study, Thoracocentesis followed by pleural fluid analysis is the best method to diagnose the underlying etiology.3 It is a safe procedure without any complications. Through the analysis of pleural fluid, making use of the biochemical parameters and gross appearance as the major and minor criteria respectively, it is possible to directly diagnose the cause of pleural effusion.

Cases for which a diagnosis can’t be potentially made, pleural fluid analysis can be utilised to determining the next approach. In transudative effusions, the underlying cause should be sought and treated. In exudative effusions in which fluid analysis does not establish the immediate diagnosis, CT of the thorax should be performed. If the diagnosis is still not conspicuous after CT, pleural biopsy is recommended. Thoracoscopic pleural biopsy and histopathology can be used as alternatives for undiagnosed cases of pleural effusion.7 The main etiology for pleural effusion is tuberculous followed by CKD in the present study conducted in a tertiary health care hospital.